Below is a chapter out of my 2012 book, "Nine Feet from Tip to Tip: the California Condor through History." It covers everything we know about the type specimen of California condor, the first condor to be described for science. You'll notice two things: the collection date given in other publications is almost certainly incorrect. It was a date guessed at by Joseph Grinnell in 1932, on the basis of known Menzies journals. After finding the missing Menzies journals, I'm able to say that the condor could have been collected in either 1792 or 1794. Also, although the bird might have been collected at Monterey (or at least in Monterey County), there are some other possibilities. In other words, the only things we know for sure are that it was collected by (or for) Archibald Menzies somewhere in California in 1792 or 1794.

[The following was originally published as a chapter in: "Nine Feet from Tip to Tip: the California Condor through History." (Gresham, Oregon: Symbios Books, 2012). If you would like a free copy (PDF) of the entire book, send me an e-mail.]

* * *

Whether or not the Ascencion and Longinos birds (early descriptions of possible condors) were California condors, there is no question about the identity of the first of the species to be introduced to the scientific community. That specimen, the one from which the California condor received its first published recognition, still exists in the Natural History Museum at Tring, United Kingdom [1]. It is a fairly disreputable looking study skin of an adult California condor, but how could it not be somewhat the worse for wear? Consider that it was obtained (probably shot) in what is now California in 1792 or 1794; was aboard a sailing ship, probably stored in alcohol, for a minimum of one year and perhaps as long as three years; was prepared by a taxidermist and put on display with sunlight, dust and bugs to deteriorate it for 100 years or so; and then stored in a dark cabinet for the rest of its 220-year existence. Actually, comparing photos of it today with some taken in 1934, it looks like someone has done rehabilitation work on it sometime in the last 75 years.

If you search for information on when and where this condor was killed, you will probably find that it was obtained 5 December 1792 at Monterey, California. That was the conclusion of Joseph Grinnell, after studying the published California journal of Archibald Menzies, surgeon and botanist on Captain George Vancouver's ship "Discovery," on their around-the-world cruise in 1791-1795 [2]. Grinnell's opinion was based on two items of information: first, Menzies had only a few opportunities to collect a condor in 1792-1793; and second, on 5 December he wrote in his journal that they had shot "a new species of Hawk," the only instance in the journal where he mentioned a bird that might have been a condor [3]. Grinnell's surmise was probably incorrect. I can't provide the real date and place that the condor was procured, but I can tell you why I think Grinnell was wrong, and I can open the door to a few other possibilities.

Very little is known about this condor specimen. Presumably it was aboard "Discovery" when the ship returned to England in October 1795. It appears likely that Menzies had it in his possession until early 1796, as his mentor Sir Joseph Banks explained in a letter 3 February 1796 to the King's Home Secretary, the Duke of Portland: "Mr. Menzies [has been employed] in arranging the various articles he collected during the Voyage, a Catalogue of these I have the honor to enclose... They are now at my house, and the greater part of them quite ready to be sent any place your Grace shall choose to direct" [4].

The Duke of Portland presented Menzies' "Catalogue of Curiosities" to the King, and it was decided that the specimens listed should be placed in the British Museum. Unfortunately, the catalogue was not specific about what birds were included, but merely identified "a Collection of Birds preserved in Spirits from California &c." [5]. We can probably safely assume that the condor was part of that collection, for within a short time the bird was being examined by George Shaw, Keeper of the Zoological Department at the British Museum. In September 1797, as part of his "Vivarium naturae" series, Shaw published the first description of the California condor. Shaw gave minimal information about the origins of the bird: "This Vulture was brought over by Mr. Menzies during his expedition with Captain Vancouver, from the coast of California, and is now in the British Museum" [6] So far, no one has found any additional data. Of Menzies' bird collection, only one other species has proven identifiable. A pair of California quail, the type specimens, were recently rediscovered after having been misplaced for well over 100 years [7].

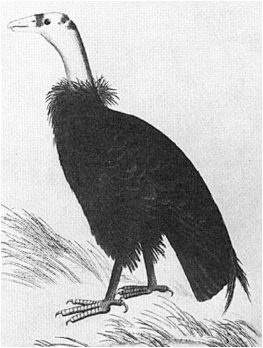

Figure 3. First depiction of California condor: Shaw's Miscellany

In the 1970s, when I was first investigating California condor mortality, I corresponded with Richard C. Banks of the National Museum of Natural History, concerning Menzies' condor. Dick expressed doubts about Grinnell's conclusions. He wrote to me: "I think it highly unlikely that a naturalist of Menzies' stature, who gave excellent descriptions of many birds in his journals and even applied manuscript scientific names to some, would have passed off the Condor as merely 'a new species of hawk' and not made some other comment... I have scoured through Vancouver's journal, and nowhere does he mention anything that might be a Condor, though he has a good bit of information including mention of two kinds of eagles, cranes, swans, ducks and teal, etc. Anyone who could separate ducks from teals would surely separate Condors from anything else."

At the time, I knew little about Menzies and his qualifications as an ornithologist, but agreed with Dick that "a new species of hawk" was an odd way for anyone to describe a condor. Still, Grinnell was correct in his statements that Menzies had few chances to collect birds in California in 1792-1793, and that Monterey in December 1792 seemed a likely place and time to have obtained the condor. Whatever my and Dick's doubts, there seemed to be no way to further the discussion. Then, in September 2008, in the archives of the National Library of Australia (Canberra), I located Menzies' unpublished journal for 1794-1795 [8]. Apparently no one interested in Menzies' natural history observations in California knew of the existence of this manuscript. Finding it opened the door for a new look at Menzies' condor.

Figure 4. The type specimen of the California condor. Photo courtesy of theNatural History Museum (Tring, United Kingdom).

Would Menzies have called a California condor "a new species of hawk?" It seems unlikely. Although Menzies' principal training and interest was in botany, his journals show that he had a wide knowledge of natural history, and that he could identify many birds by type, if not by species. Typical of his written comments: "We also saw a number of Birds such as Auks Divers & Shags" [9]. "We shot several Plovers and other small birds. We saw on the Lagoon large flocks of Pelicans & vast flights of common Curlews flying about..." [10]. But other notations show that he was much more than just a "bird watcher:" "On rowing a little distance from the ship I shot one of the large brown birds which were at different times seen in the course of this passage & found it to be a species of Albatross agreeing nearly in its characteristics with the Diomedia fuliginosa but as I was somewhat doubtful of its being the same bird, I have here subjoined the following brief description of it. This bird is about 7 feet between the tip of its wings moderately extended / & three feet in length including the Bill which is 4 inches & of a chocolate colour, the upper mandible is longer than the under & hookd at the end: The front--a small spot under each eye pointing backwards; the rump, crissum inner half of the tail & shafts of the quills are white; the rest of the head neck & tail together with the upper parts of the body & wings are of a dark brown, but the gullet & belly are of a dusky cinereous colour; the legs toes & claws are black; the trides dark hazley" [11].

And on another occasion: "...the Vessels had been visited by a few Natives who had nothing to dispose of but a few Water Fowls particularly a brackish colourd species of Auk with a hornlike excrescence rising from the ridge of its Bill, & as it appeard to be a new species I named it Alca Rhinoceros & describd it" [12].

A person who could make these kinds of observations seems like someone who could tell that a condor was a type of vulture, not a hawk. In fact, Menzies' journal entry at Monterey 29 November 1794 shows that (at least by the end of the voyage) he did know.

"The country swarmed at this time with a vast variety of birds both land & aquatic; many of them had migrated to these regions from the northern parts of the coast, to [escape?] the severity of the weather. Among the larger were eagles hawks vultures two species [my underlining], cranes white & blue, Canadian Geese, Ducks, Teal, Widgeons, Quails, Plovers, Curlews, Ravens Crows etc. & of small birds a numerous catalogue; so that sporting parties had sufficient amusement, in addition to the variety of excellent repast afforded to our tables by their industry" [13].

The two species of vultures could only be the California condor and the turkey vulture, and the "new species of hawk" was probably a species of hawk. There would have been a number of possibilities at Monterey in late fall but, without Menzies' list, there is no justification to speculate.

* * *

As pointed out by Grinnell, there was limited opportunity to obtain specimens in California in 1792-1793, even taking into account that Menzies was not the only one in the party killing birds. Still, there was ample time at several locations to kill a condor if one had been available. Also, Grinnell did not know about the 1794 visit, which offered additional chances.

The Discovery was in San Francisco Bay 15 November to 25 November 1792. Menzies was recovering from a serious illness, and only took a few short walks near the bay shore during that time, but Captain Vancouver and some of the crew were three days on horseback visiting the Mission Santa Clara [14].

At Monterey 27 November 1792 to 14 January 1793, Menzies and others spent considerable time on shore. He noted in early December that "those who were fond of shooting & sporting were suffered to indulge in their favorite pursuits without the least restraint, so that parties were out daily traversing the Country in almost every direction for ten or twelve miles round" [15]. After his walk to Point Pinos on 5 December (the day they collected the "new species of hawk"), Menzies wrote: "The two following days I remaind on board examining drawing & describing my little collection & such other objects of natural history as were brought me by the different parties who traversd the Country, & who were in general extremely liberal in presenting me with every thing rare or curious they met with. The sporting parties were particularly successful in killing a vast variety of Game with which the Country abounded & which were now in full perfection" [16].

From Monterey, the Discovery sailed to the Hawaiian Islands and did not return to California until 2 May 1793, when they landed at Trinidad on the far northwest coast. They stayed two days, but apparently no one ventured far from the ships, and all were busy taking on water and refitting the vessels. The expedition went north from Trinidad, and did not touch land in California again until 20 October 1793, when a party including Menzies landed at Bodega Bay for a short visit. Menzies wrote: "We strolled about on the low land between the Bay & the Lagoon which was composd of sandy banks & small hillocs on which we shot several Plovers & other small birds. We saw on the Lagoon large flocks of Pelicans & vast flights of common Curlews flying about, but both were so shy that we could not get near enough to have a shot at them" [17].

At San Francisco Bay 21-24 October 1793, Menzies did not leave the ship. Some of the crew went ashore, but the Spaniards were much less hospitable to the English than on their previous visit, and no one went far. Similarly at Monterey 1-6 November, the Spaniards were uncooperative, and apparently no observing or collecting were done on shore. The Discovery was welcomed at Santa Barbara, and in the period 10-18 November 1793 Menzies made several trips into the countryside on foot and horseback. He noted on 12 November that "the thickets swarmd with squirrels & quails & a variety of other birds which afforded some amusement in shooting them as I went along... I did not persevere to gain the summit of the ridge but returnd on board in the afternoon with what collection I was able to make of Plants & Birds" [18].

The expedition put in at San Diego 27 November to 9 December 1793, but the Spanish would allow the English on shore only between the beach and the presidio. Menzies wrote that he botanized, but there is no indication that any bird collecting was done. From San Diego, the ships returned to the Hawaiian Islands.

Menzies' last visit to California occurred in November 1794. The Discovery reached the Pacific coast near Cape Mendocino on 3 November, and headed south. The expedition had intended to visit Drake's Bay, but bad weather prevented the side trip. They bypassed San Francisco Bay, and arrived at Monterey the afternoon of 6 November. This time, the Spaniards were friendly, and the exploring party was given unrestricted access to the area. A number of days were taken up with diplomacy and working on the ships' supplies, but between 9 November and 29 November, Menzies "continued making almost daily excursions in various directions." He mentioned riding to Mission San Carlos, and to a hill some 12-15 miles east of Monterey. We know from Capt. Vancouver's writings that some of the party made a longer trip into the interior, perhaps reaching the San Benito Pinnacles, later found to be a nesting area for condors. Menzies did not make mention of that trip in his journal, and apparently stayed at Monterey. The Discovery departed Monterey 2 December 1794, finally on its way back to England. No other stops were made in California or Baja California [19].

Menzies' condor could have been collected at Trinidad in May 1793; at Bodega Bay in October 1793; around San Francisco Bay November 1792 or October 1793; at Monterey November or December 1792, January 1793, November 1793 or November 1794; at Santa Barbara November 1793; or at San Diego November or December 1793. Because it would only take an opportunistic moment to kill a condor, none of those places or times can be completely ruled out. Practically speaking, the hostility of the Spanish government in 1793 severely limited the possibilities at San Francisco and Monterey. There was very little time at Trinidad in 1793, and the short time at Bodega Bay in 1793 was well-documented in Menzies' journal without reference to condors. San Francisco Bay in 1792 and San Diego in 1793 were better possibilities, although the restrictions imposed by the Spaniards at San Diego certainly reduced travel and (probably) collecting activity. By far, the best opportunities to procure a California condor would have been at Monterey during the winter of 1792-1793, at Santa Barbara November 1793, or at Monterey November 1794.

Of the three possibilities, perhaps the first visit to Monterey is the least likely. One would think that acquiring a California condor would be more noteworthy than "a new species of hawk," and would have been granted some acknowledgment in Menzies' journal. The only reason to give Monterey in November 1794 a slight edge over Santa Barbara in November 1793 (both of which were logical locations at logical times) is that the last visit to Monterey was the only time in his journal that Menzies mentioned vultures. The evidence is too slim, however, to rule out Santa Barbara.

* * *

It was a rare writer in the 19th century who did not wax eloquent at merely the sight of a California condor. One has to wonder why Menzies - one of the first Europeans to see, let alone possess, a condor - did not mention the bird in his journal, and why we only know about the specimen because it still exists, and because an 18th century zoologist published a brief description of it. I think the answer is that there are - or were - more of Menzies' records to be found.

Menzies' journals include various comments on fauna and flora observed, but most of them are rather general. He seldom mentioned a specific collecting incident, and even his botanical notes are often superficial. Reading through the journals, I come away with the impression that he was recording specific details somewhere else. For example, at San Francisco Bay 15 November 1792, he wrote: "I saw likewise [in addition to plants] several Birds which were new to me, but I shall be able to speak of them more particular hereafter" [20]. Nowhere in his known journals is there any further elaboration. Of his examination of a rhinoceros auklet in Washington's San Juan Islands on 6 June 1792, he wrote: "...as it appeared to be a new species I named it Alca Rhinoceros & describd it" [21]. The description has not been found. We don't know how many specimens actually reached England, but his "Catalogue of curiosities" included "a collection of birds," which to me implies more than one California condor and two California quails. We know from his journals that he regularly collected birds, and that other people brought him specimens. He wrote about "examining drawing & describing my little collection," but those details are not included in any known documents. Much points to Menzies keeping two sets of notes, as later scientists (myself, included) often did. The "journals" have been found, the "species accounts" have not.

Controversy surrounds various logs and journals written by other members of the Vancouver expedition. Portions of these are missing, or are written in much less detail than one would expect, and there has been speculation that sections were purposely destroyed to suppress evidence of a certain controversial disciplinary action aboard ship. Menzies' 1794-1795 journal was thought to have fallen victim to that same suspected purging of evidence. Vancouver did, in fact, order Menzies to give him his journals, but this may have been more an issue of jealousy and chain of command than part of any other controversy. Although a member of Vancouver's staff, Menzies had received his orders from Sir Joseph Banks, and was directed to give all of his papers and specimens directly to Banks. Menzies refused to give his records to Vancouver, and may have sent some of his materials to Banks even before the expedition ended. He wrote to Banks from Valparaiso, Chile, in April 1795:

"When the Journal of the Voyage etc are demanded by Captain Vancouver I mean to seal up mine and address them to you, so that you will receive them I hope through the same channel as the most part of my correspondence during the Voyage" [22].

From Ireland, just before the end of the voyage, he again wrote to Banks: "Though Captain Vancouver made a formal demand of my Journals etc before he left the ship; I did not think myself authorized to deliver them; in my present situation [he was in the brig for insubordination] particularly till I should hear from you or the Secretary of State from the Home Department; when I shall be ready to deliver up everything I have written, drawn or collected during the whole voyage, agreeable to the tenor of my instructions" [23].

Menzies' "insubordination" may have saved his 1794-1795 journal from destruction, and it seems likely that it never became an official part of the expedition record. Although his specimens were presented to the British Museum in early 1796, Menzies was still working on finalizing his reports on the trip two years later. He wrote to Sir Banks in January 1798: "My sincerest thanks for your friendly admonitions and solicitations respecting the finishing of my Journal before Captain Vancouver's is published. It is what I most ardently wish, for more reasons than one, and therefore have applied to it very close... The Volume I am now at work upon (and which is nearly finished) I once thought would include the whole of the remainder of the Narrative, but I find it will not, although it is much larger than either of those you have got" [24].

In June 1798, he apologized to a friend for not answering his correspondence, attributing the delay "to my being so much occupied on the business of our late voyage" [25]. In 1799 he was appointed surgeon on HMS Sanspariel, and did not return from the West Indies until late 1802. Shortly after, he married and opened a surgeon's practice. It may be that, with the passage of time and the press of other business, Menzies never finalized some of his accounts from the Vancouver Expedition. The fact that I found the 1794-1795 journal among the Banks archives in Australia offers some hope that other Menzies papers may yet be rediscovered.

* * * *

One might ask why the British Museum did not keep better records of Menzies' collections. The answer seems to be that, from its beginnings in Dr. Hans Sloane's Museum in 1753 into the early 19th century, the institution was very poorly run, not an unusual situation for early museums. Many specimens were lost through lack of care, and records were superficially kept [26]. The first catalogues of ornithological specimens were not prepared until the 1830s. Prior to that, the only records for bird accessions were the Minute Books of the Trustees' Standing Committee (where the note on Menzies' "catalogue of curiosities" was found) and donation records, the Catalogue of Benefactors to the British Museum. Unfortunately, the "Benefactions Book" is not "the contemporary, up-to-the-minute, record which might be assumed but was compiled after the Trustees' Meetings, probably at times a good deal after the meeting. The Trustees resolved on 27 June 1760 that the Benefactions Book be written up when there was sufficient copying to employ the writer for one day" [27]. Apparently, the Menzies data (if there ever was any further information given to the Museum) got lost along the way.

Chapter Notes

1. Page 52 in: Knox, A. G. and M. P. Walters. 1994. Extinct and endangered birds in the collections of the Natural History Museum. London, England: The British Ornithologists' Club.

2. Eastwood, A. 1924. Archibald Menzies' journal of the Vancouver Expedition. California Historical Society Quarterly 2(4):265-340.

3. Grinnell, J. 1932. Archibald Menzies, first collector of California birds. Condor 34(6):243-252.

4. This letter is in the Botany Department, Natural History Museum (Tring, United Kingdom), Joseph Banks Correspondence, Dawson Turner transcripts 10:15-16; the portion quoted was reproduced on page 23 of: Galloway, J. D., and E. W. Groves. 1987. Archibald Menzies MD, FLS (1754-1842), aspects of his life, travels and collections. Archives of Natural History 14(1):3-43.

5. The "Catalogue of curiosities" is included as Item PN1 in the Sir Joseph Banks collection of the Sutro Library (San Francisco, California). My thanks to Martha Whittaker, Sutro Senior Librarian, for examining the files for me. The entire list of "curiosities" is included in: Dillon, R. H. 1951. Archibald Menzies' trophies. British Columbia Historical Quarterly 15(3-4):151-159.

6. Shaw, G., and F. P. Nodder. 1797. Vivarium naturae, or Naturalist's Miscellany. Ninth volume. London, England: Nodder and Company.

7. California quail information from Robert Prys-Jones (Head, Bird Group, Natural History Museum, Tring, United Kingdom), who will publish details.

8. Menzies, A. 1794-1795. Journal of Archibald Menzies, 1794-1795. Unpublished manuscript in the collections of the National Library of Australia [Canberra, Australia], 260 pages.

9. Page 4 in: Newcombe, C. F. (editor). 1923. Menzies' journal of Vancouver's voyage April to October 1792. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: British Columbia Provincial Library.

10. Eastwood op. cit., page 303.

11. Newcombe op. cit., page 3.

12. Newcombe op. cit., pages 46-47.

13. Menzies 1794-1795 op. cit.

14. Menzies' itinerary in 1792-1793 is from Eastwood op. cit.

15. Eastwood op. cit., page 285.

16. Eastwood op. cit., page 286.

17. Eastwood op. cit., page 303.

18. Eastwood op. cit., page 317.

19. Menzies 1794-1795 op. cit.

20. Eastwood op. cit., page 268.

21. Newcombe op. cit., pages 46-47.

22. Galloway and Groves op. cit., pages 21 and 38.

23. Galloway and Groves op. cit., pages 22 and 38.

24. Letter to Sir Joseph Banks 3 January 1798, from Archibald Menzies. Included in archive Letters of Sir Joseph Banks, Series 61, Number 35. State Library of New South Wales (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia).

25. Galloway and Groves op. cit., pages 25 and 38.

26. Pages 83-84 of Sharpe, R. B. 1906. Birds. Pp. 79-515 in The history of the collections contained in the Natural History departments of the British Museum, Volume 2. London, England: Trustees of the British Museum.

27. Wheeler, A. 1996. Zoological collections in the early British Museum--documentation of the collection. Archives of Natural History 23(3):399-427.

LEAVE A COMMENT: symbios@condortales.com